Galluses.

This was my word of the week.

If there was any suspicion out there as to whether or not the words I have been receiving so far are in fact truly random, I hope this sets, in the words of the late, great Mr Presley, suspicious minds at ease. Because, let me tell you, when I opened my word of the day email, and saw, after putting on my glasses, and realising it was not, as first squinted at, ‘calluses’ sitting on the screen, the first thought to mind was this.

Oh, poop on a plate.

The second, despite having the definition right there, was “what on God’s green earth is/are galluses?” Calluses made of gallstones? Gallstones made of calluses? Galoshes with a spelling problem? A sea-sick penis?” (snort). Because, let me tell you, the definition was so uninspiring, I was already making a more interesting one up, just for the hell of it – although I am not sure how any of the above fit into talking about chronic illness.

Still. It was fun trying.

Galluses, (n.) for those now desperate to find out the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, are in fact the following:

1. Older Use. a pair of suspenders for trousers.

See what I mean?

As I was staring at this word, thinking “well, that’s it – no words for me today” – a sudden and fierce mental image punched me to a TKO, as surely and comprehensively as though I was Foreman facing Ali’s rope-a-dope. And I realised this was, as suspected, going to be a freakinghard word to write something about, but not in the yawn and stretch, stare blankly at blinking cursor way I had expected. Instead, it was going to mean bouncing off the ropes, a true rumble in the memory jungle; avoiding constant hits of sentiment and love just to get to the end of the round.

I say round, because with this fight – I know I cannot win.

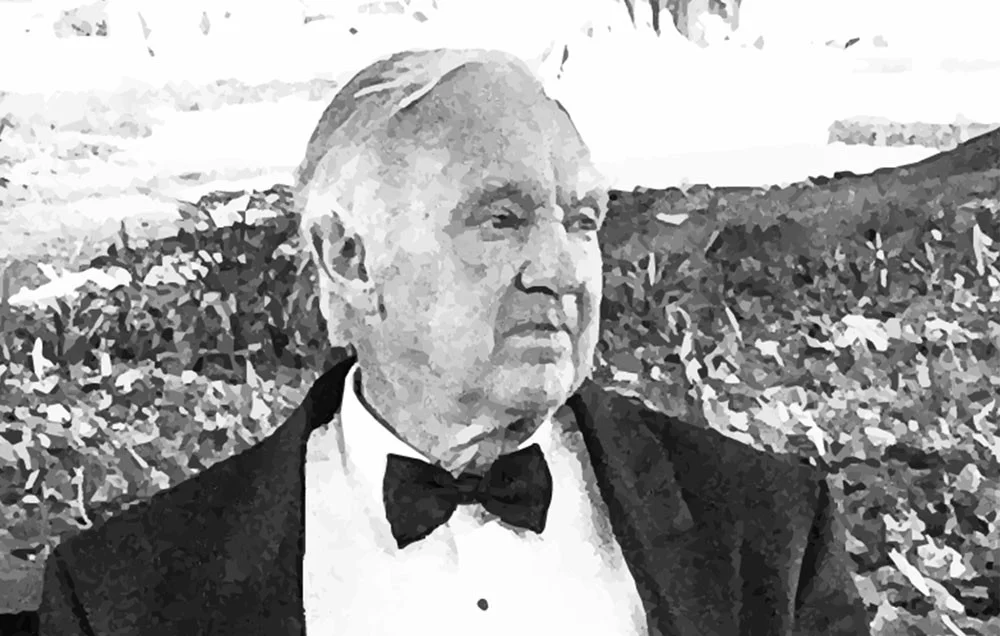

My father. My father is a good man. There are many words other than ‘good’ I can use to describe him, none particularly complimentary; impatient, fastidious, short-tempered, irritable, demanding of perfection – mainly in and of himself. Then there are others. Quiet. Shy. A doer of incredible things for others, in the background, without them noticing, and without looking for recognition. A total tech nerd. An armchair referee, which explains a lot about my own habit of swearing black and blue at rugby officials. A damn good sportsman in his time. An appreciator of meaty red wines. A man who remains appalled, although now somewhat resigned, at my gutter mouth, because his idea of hard swearing is ‘bloody hell’.

Someone who, until he isn’t there, you don’t really notice – but as soon as he’s gone, you wonder at the sudden lack of presence.

I love him. He is a good, good man. He is my dad. He is a still eye in the hurricane of lunacy which is my mum and I, and our ability to talk the world into a corner and under the table with its fingers in its ears before breakfast.

He is an extremely natty dresser. Always has been. So much so that I would, at university, raid his wardrobe for his beautiful (and extremely expensive) cotton shirts, then attempt to sneak them back in without being found out. This never worked, despite my fooling myself it did.

He has terminal cancer.

One of the first things his oncological surgeon told him, when he and my Mum were given the initial diagnosis, was this; he had to have a colostomy. No if, buts, ands, or maybes.

This, I think, was more distressing to him than any other part of what he had to take in; limited time frames, harsh and painful treatments, anything. It meant loss of independence, of potential mess, of an interruption to his extreme fastidiousness. It meant possible reliance on others, and it meant he may not be able to play golf (equivalent to world being doomed, apocalypse on way, cockroaches taking over planet).

What it has meant in reality is a man whose engineering and analytical skills, which have been turned to many and varied things in their time, being now turned to how best manage something many people would turn their backs to the wall about.

It has also, as a practicality, meant he can no longer wear belts. I remember talking to him about the problem when he first had the bag fitted. He said “I’m having issues… I can’t get my trousers to sit properly. The belt gets in the way of the bag, and they’re falling down.” (The man is whippet thin). I said to him “Why don’t you try suspenders? You know, braces?” He scoffed, and said “And look like a bloody twit?” After a great deal of eye-rolling on my part, and reassurances he would, in fact, look decidedly spiffy, he got his first pair.

He now has a great many of them.

Festive ones, everyday ones, dressy ones – my Papa, king of the galluses. They suit him. He is stylin’. A throwback to the age of sharp suiting, when men doffed hats, and women checked their stockings to see if the seams were straight.

I try not to think of the fact that he is shrinking within them like a shadow before my eyes.

It’s pretty messed up when an illness provides a bond between a parent and a child. But in this case, I have been glad, if glad is the right word to use in these circumstances. My father finds it difficult to talk of personal issues at any time. He is not an openly affectionate person, not due to a lack of love for his own little family, but because of an upbringing by parents who make Roald Dahl’s Wormwoods look like angels.

I think the first time he told me he loved me was in about 2004, which may give some indication of his ability to communicate openly on any kind of deep level. But when he was diagnosed, his knowing I had been through the whole shitpile that is cancer helped him, I think, to talk about it in a way he couldn’t talk to my Mum – because he could yak about practicalities. The nausea. The fact everything tasted like tin. How tired he was. How much he hated this tablet, and that tablet, and had I taken this one, and did it do this to me, because it did this to him.

Mum is also a super-tard when it comes to remembering names of medications, so to have someone else with his kind of recall for the small details was important to him. It meant a focus on the unemotional, rather than the ‘I’m dying’.

In many ways I feel like I have committed a crime, because I have beaten back the beast three times, and my dad is not going to. As if by being fortunate enough to be allowed three shots at survival, I was greedy, and took his away.

He has found it exceptionally hard to deal with the more physical symptoms of my Parkinson’s, because it has been distressing to see his daughter in pain, or struggling with the unknown. I wish I could tell him how much it is in turn destroying me to watch what is happening to him, but that’s not fair. It would hurt him, not help him. Instead I tend to be sharp when he is down, and tell him off. He and my mum are the breadth of a country away, and when we speak, I ask how he is, and then I give him a hard time about something or other, usually his footy team, or being lazy, or something of equal ridiculousness, to make him snarky and gee him up.

It is a suspension of reality. Just as his snappy galluses hold his trousers onto his ever-shrinking frame, our elastic and expandable conversations of what looks to outsiders like rudeness are, to us, holding our world together.

My father is the definition of a pair of suspenders. Useful, often forgotten about, comfortable and practical. Old-fashioned, but stylish and suitable for all occasions.

And, like me, if he saw that word of the day, he would have said “what the bloody hell is that?” – and then found a use for it. Because that’s what we do, he and I. Find a practical solution to the seemingly insurmountable.

All I need to do now, of course, is find a way to gallus – or suspend – time, before his body and mind’s braces lose their physical and mental elasticity and he is just too tired to keep the pain and the lure of Morpheus’ eternal embrace away.

You know I want too, Dad. I’m rolling up the sleeves on one of your best shirts, and giving it a red hot go.

I can hear you swearing from here:

“Which bloody shirt??”

Excellent. I just twanged your galluses. There’s fight in the old bugger yet.